Anne Rice Returns to her Faith

Anne Rice shocked her fan base in 2005 by releasing a hagiographical novel about Christ, imagining his early life and the Jewishness of his family and roots. She followed that with Christ the Lord: Road to Cana earlier this year, taking the story up to the beginning of Jesus’ adult ministry. Reviews have been mostly positive, with a small but critical minority bemoaning Rice’s newfound zeal and the drastic turn she has taken from the vampire fiction that made her famous. When, the naysayers asked, did Anne Rice get religion?

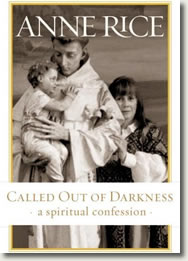

Here is their answer. Curious fans, devout Catholics, and undecided spiritual seekers alike will find something valuable in Rice’s new spiritual memoir, Called Out of Darkness.

In it, she details the transformations inherent in becoming what she calls “a writer consecrated to Christ,” who has turned her back on the achingly lonely fiction of The Vampire Chronicles, not to mention the erotica she has penned under other names.

The first half of the memoir is a thick description of the sensuality and visual feast that was her Catholic childhood. Rice discusses how it was Catholicism, not books, that first shaped her as a writer. Whereas other writers were early and voracious readers as children, Rice reveals that reading was a chore for her well into adulthood, but that Catholicism—with its visual opulence, evocative sounds, and tantalizing smells—fused itself to her imagination from the beginning.

The New Orleans of her childhood was a vibrant, thriving place precisely at the time when Catholicism was on the ascendant in postwar America. Rice also discusses how television, film, and radio shows shaped her soul and sparked her imagination. With those influences, and parents who were first-generation intellectuals who encouraged their daughters' wild creativity (even to the point of allowing them all to rename themselves, as “Anne” did when she started school), an innovative and original life seemed inevitable.

As with many creative people, Rice’s push on the boundaries of imagination led her to also question her church, her inherited faith, and even the existence of God. She jettisoned her Catholicism in college like a reptile shedding its skin in the light of a new sun. She did not look back for thirty-eight years, embracing atheism as natural and right in contrast to the ludicrousness of belief. Still, Rice reveals, there were some things she never quite abandoned, including her love for religious art and her desire to go on pilgrimages all over the world—a desire she indulged many times.

By the late 1990s, Rice was almost compulsively buying up churches and religious properties in her hometown of New Orleans and beginning a slow but beautiful return to faith, the discovery of which takes up the second half of the memoir. Readers who are familiar with the progression of James Fowler’s various “stages of faith” will observe the almost textbook evolution of Rice’s religion, including the conventional acceptance of received truths (stage three), the rejection of those beliefs in the struggle for self-definition (stage four), and the joyful synthesis that is possible when one discovers the divine (stage five).

When Rice did return to Catholicism, it was to a post-Vatican II Church with its English mass and more ecumenical leanings, as well as a denominational crisis in the form of emerging pedophilia scandals. Rice found the adjustments and problems disorienting but the essence of Catholicism was, for her, unchanged: Christ was present in the mass, there on the altar, waiting for her. In the memoir she waxes fairly rhapsodic about the mystical union that is possible with Christ, sounding at times like a modern-day Saint Teresa of Avila.

In some ways, the book is shockingly impersonal. It is a rumination on religious faith, not a writerly tell-all, so readers shouldn’t expect to find behind-the-scenes career details of how Rice got published (it’s barely mentioned), how she regarded the film adaptation of Interview with the Vampire, or how she feels about her tremendous commercial success. Also missing are intense personal details like how Rice’s faith might have been tried by the devastations of Katrina in 2005, shortly after she had left her native New Orleans, or the earlier and more private despair she felt when her young daughter Michele died of leukemia in 1972.

Both Michele’s life and her death are almost like a footnote in Rice’s story, with no reflection on either. In an otherwise deeply contemplative, even broody, memoir, such a lacuna feels like a glaring omission, but the reader gets the distinct impression that some events in Rice’s life are simply too painful for her to discuss. Other difficult trials, like her mother’s alcoholism or her husband’s death in 2002, are discussed but by no means dissected. The memoir shows a quiet restraint, which some people, perhaps especially those of Rice’s generation, will find refreshing.

Copyright ©2008 Jana Riess