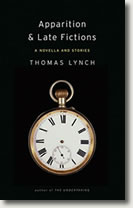

Apparition and Late Fictions: A Novella and Stories

by Thomas Lynch

W.W. Norton & Company

February 2010, $24.95 hardcover

Thomas Lynch is one of those writers who have always had another career besides writing. Most of us do, but often, the successful ones, like Lynch, don’t. There are a few famous exceptions. T. S. Eliot, for instance, was a book publisher. That’s interesting, but it also relates to his work as a writer. More intriguing are those like the poet Wallace Stevens, who was a lawyer for an insurance company. Or William Carlos Williams, another of America’s great modernist poets, who was also a pediatrician.

Lynch, 58, is an undertaker. This wouldn’t seem to be an occupation that draws the same sort of person as does the work of writing poetry and fiction, but Lynch has found his way in all of these things and with tremendous results. It turns out that the funeral home business, which he’s run in a small town in Michigan for decades, has provided a wealth of insight into death —and that’s what Lynch writes about best.

Death is the primary subject of this new collection of stories, just as it was of his 1997 book of essays, The Undertaking: Life Studies from the Dismal Trade, which won Lynch both awards and recognition, including the American Book Award.

Apparition and Late Fictions is not only about death, but about missing children, former spouses, dogs (lots of dogs), AA meetings, loss, and redemption. One story tells of a widower who has survived three marriages and made a bundle of mistakes in each of them. The man is a salesman for a casket company. In another—the first story in the collection, called “Catch and Release”—Danny, a fly-fishing guide in western Michigan, takes a thermos bottle with his father’s ashes out on his drift boat one afternoon. As he remembers his father, he fishes, and slowly distributes the ashes into the water that the two of them had shared. It’s clear that Lynch knows how to fly-fish, and that he’s also a poet, in passages such as this one:

He could feel the split shot in the gravel at the top of the hole, and could feel it fall into the deeper run, and watched the loop in his line straighten in the current and held the rod out in front of him as the line moved through the water.

He also writes beautifully about human bodies, and the ways in which we think about our bodies. In one story, the narrator reflects on a young woman’s feelings of happiness and how they relate to her “graceful body and eyes like the blue of the indigo bunting.” In another, a lithe, young intellectual on a cross-Atlantic flight is appreciating the male flight attendant, whom she assumes, to her disappointment, to be gay: “She could see that he paid attention to his body hair and the press of his trousers. But if he weren’t [gay], she wondered, which of her parts would his hands first go to.” I suspect that these insights come from Lynch’s lifetime of talking with family members about how to best present their loved-ones for viewing in a casket. But Lynch is at his very best when he moves from death back to life, and when he shows us how to do the same.

In “Catch and Release,” before Danny dispenses with the last bit of his dad’s ashes (I won’t tell you how), the narrator summarizes what has been a subtext to the memories of father and son: a trusted dog with a bad leg that most everyone believed Danny should have put to sleep. In the drift boat on that afternoon, Danny and his dog, Chinook, have arrived at a memorable place:

Danny wondered if the dog knew how close it had come to being killed in this place. It was to [here] Danny had brought the dog two years before, after all the experts had weighed in with their advice. They’d fished all day and Danny climbed the high banks to the oak ridge from which he and his father had first looked down on the curling braids of river that formed the swamp that winter years ago when he was eight. He had a field shovel and a pistol he had borrowed from a fellow guide. At the top, he began digging the dog’s grave, the work quickening with anger and slowing with sadness, the variable speeds of the labor like the division of his heart. He had the grave dug, the pistol loaded, the blanket he intended to wrap the corpse in ready. He whistled for the dog…. “C’mon, Chinook,” Danny called, and the dog ran the bank upstream fifty yards, then dove into the current, crossing to a sandbar in the middle, shook himself dry, then dove again, swimming upstream fifty more yards before coming to the base of the high banks. He shook himself dry again and bounded up the steep hill without slowing. At the top of the high banks he leapt into Danny’s embrace. This prodigious bit of cross-country swimming and sprinting and climbing, regardless of the crookedness of his leg, proved the dog well able for his habitat. It convinced Danny that he should not kill him, now now, not ever.

When an earlier American short story writer—Flannery O’Connor— was asked why she wrote about such odd characters, she said, “We’re all grotesque.” I suspect that if someone asked Thomas Lynch why he writes so often about death, he’d say because we are made to live.

To learn more about Thomas Lynch visit www.thomaslynch.com.

Jon M. Sweeney is a book publisher and writer living in Vermont. His most recent book is Cloister Talks: Learning from My Friends the Monks (Brazos Press).