David Bazan: Artist, Sinner, Christian

The Christian [artist] will find in modern life distortions which are repugnant to him, and his problem will be to make these appear as distortions to an audience which is used to seeing them as natural; and he may be forced to take ever more violent means to get his vision across to this hostile audience. When you can assume that your audience holds the same beliefs as you do, you can relax a little …[but] when you have to assume that it does not, then you have to make your vision apparent by shock - to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large startling figures.

— Flannery O'Connor

Named one of the top 100 living songwriters by Paste magazine, David

Bazan (formerly Pedro The Lion) has produced some of the most compelling musical

narratives of hypocrisy, despair, and grace over the last decade. His work—as

unique and noteworthy as that of any of his contemporaries— springs from a

deeply held Christian conviction that often finds itself at war with the

Christian culture. Writing, as he does, about misplaced pride, adultery,

domestic violence, religious hatred, and countless other effects of sinfulness,

he unsettles the comfortable and downright unnerves the legalistic.

Named one of the top 100 living songwriters by Paste magazine, David

Bazan (formerly Pedro The Lion) has produced some of the most compelling musical

narratives of hypocrisy, despair, and grace over the last decade. His work—as

unique and noteworthy as that of any of his contemporaries— springs from a

deeply held Christian conviction that often finds itself at war with the

Christian culture. Writing, as he does, about misplaced pride, adultery,

domestic violence, religious hatred, and countless other effects of sinfulness,

he unsettles the comfortable and downright unnerves the legalistic.

For Bazan, sin is a real category, not just Freudian guilt or some random mechanism of evolution, but rather a conscious choice made in offense to God, having both eternal and temporal consequences. He writes as someone who knows “how far the curse is found” and doesn't shy away from giving us the details. Yet there are hopeful tones in his music, and grace is never too far around the corner from the gravest despair.

He is also one of the very few Christian artists to enjoy underground fame in the alternative music world. A large part of his appeal comes from the fact that he sees art as his primary vocation. He doesn't go in for clichés or sermons, choosing instead to use narratives and rants, couched in wonderfully creative musical structures. This makes him somewhat unique among Christian artists, who generally prefer to preach to the choir while replicating last year's top 40 melodies and styles.

Musically I'd put Bazan in the company of Elliott Smith or Tom Waits. Spiritually I'd put him in the company of Flannery O'Connor and Walker Percy. Tempermentally he reminds me of a Christian version of Charles Bukowski crossed with the Dude from The Big Lebowski. He's a man for his time, reporting back from the edge of faith to those of us lacking a good vantage point from which to see ourselves.

With an astute ear for a good tune and a critical eye for spotting hypocrisy, he tempers his lyrics with a good dose of his own failings. If you had to sum him up, you might say he functions as a sort of rock n' roll Hosea, the minor prophet commanded to live with the prostitute wife.

For Bazan, telling the truth about sin, in all its ugly reality, is an imperative. Like the Biblical prophets of old, he puts a high value on transparency and “calling a spade a spade,” and like Flannery O'Connor, he's not afraid to use some harsh subjects and harsh language to get the point across. To give one poignant example, in the song “Rapture” he conflates the sexual gratification of a man committing adultery with the ecstasy of a person experiencing union with God. The juxtaposition, one can only assume, is meant to highlight the ridiculous folly of the act.

This sort of writing admittedly makes many people uneasy. Religion, politics, sex, Christian culture— nothing is spared in Bazan's quest to speak truth into situations, and no method is too strong to get his point across. This is especially true when he attacks hypocrisy. Take for example the lyrics to his song “Magazine,” where he describes the narrow path between Pharisaeism and license, and the consequences of missing the mark to either side.

This line is metaphysical

And on the one side, on the one side

The bad half live in wickedness

And on the other side, on the other side

The good half live in arrogance

And there's a steep slope

With a short rope

This line is metaphysical

And there's a steady flow

Moving to and fro

Bazan has a keen eye for pointing out examples of when people start calling distorted versions of the faith normal. In the song, “Secret of the Easy Yoke,” the narrator talks about feeling alienated at church, attending but not hearing the gospel, not finding rest for her soul. As she begins to give up on faith toward the end of the song, a refrain rings out, and Bazan quietly begins to echo the words of Christ in the storm, “peace be still,”over and over again until the song fades out.

The devoted were wearing bracelets

To remind them why they came

Some concrete motivation

When the abstract could not do the same

But if all that's left is duty

I'm falling on my sword

At least then I would not serve

An unseen distant lordIf this is only a test

I hope that I'm passing

Cause I'm losing steam

And I still want to trust you

Peace be still

I find this music strangely comforting. It smacks of reality to me, and even though it confronts me with some tough questions and accusations that are depressing, it also inspires me to be mindful of those around me, particularly with regard to how Christ would treat them. There's a certain type of solidarity you feel in knowing you're not the only one who thinks this way, and there's also peace in knowing that Christ's love transcends the sinfulness of his people. It's a shame that more art doesn't engender the same prophetic spirit.

Unfortunately being prophetic often doesn't win you too many friends, especially if the methods you use are abrasive. Bazan accordingly finds himself stuck between two worlds. The mainstream rock community makes fun of him because he talks too much about God, and the religious establishment doesn't want him because his brand of transparency makes their demographic uncomfortable. There isn't a niche for him to fill, and as a result he frequently finds himself expending a great deal of energy to explain his work to both camps.

Over the last couple of years, it appears that the compounding pressure of being stuck between the polar expectations of these two communities has pushed Bazan past prophecy to the point of personal anger. You can hear his frustration boiling over in recent songs like “Foregone Conclusions,” the lyrical tone of which is furious. The narrator has had it with Christians over-spiritualizing issues and judging without taking the time to understand.

And you were too busy steering the conversation toward the Lord

To hear the voice of the Spirit,

begging you to shut the f*** up.

You thought, it must be the devil,

trying to make you go astray.

And besides, it could not have been the Lord

Because you don't believe he talks that way.

And after all, you and I are nothing more than foregone conclusions.

Say what you want about the use of the F-word here, this song raises good questions about the problems created when anyone spiritualizes life too much. And this is really what makes the work of David Bazan important at the end of the day. He reminds us that art exists not only to tell us who we should be, but also to show us who we are. By revealing that sin exists just as much within church walls as without, he tears down the dividing wall between the two cultures and opens a space through which free grace extends to all, even artists.

At the end of the day, you can argue about his methods, you can say he's a bad example, and you can turn him off. But you can't ignore him, and you have to deal with the criticisms he levels against your own sinful heart. Strong medicine indeed, but it goes down easy. The music is that good.

I don't know about you, but I take comfort in that. It's good knowin' he's out there, the Dude, takin' er easy for all us sinners. Shoosh.

—The Big Lebowski

More info

can be found at the Web site davidbazan.com

Copyright ©2006 Christopher Stratton

For further listening, the author recommends:

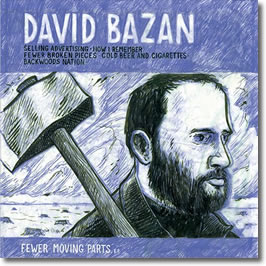

FEWER MOVING PARTS

David Bazan

IT'S HARD TO FIND A FRIEND

Pedro the Lion

CONTROL

Pedro the Lion

WINNERS NEVER QUIT

Pedro the Lion