Counting on the Enneagram

For 20 years I’ve been running a numbers game. In my attempts at enlightenment I have consulted the twelve steps (Bill Wilson), the four agreements (Don Miguel Ruiz), the seven critical choices (Dr. Phil), and the five people you meet in heaven (Mitch Albom). For a historical perspective, I also reviewed the four humors (blood, phlegm, black bile, yellow bile)—the Classical Era’s answer as to why people are the way they are.

For 20 years I’ve been running a numbers game. In my attempts at enlightenment I have consulted the twelve steps (Bill Wilson), the four agreements (Don Miguel Ruiz), the seven critical choices (Dr. Phil), and the five people you meet in heaven (Mitch Albom). For a historical perspective, I also reviewed the four humors (blood, phlegm, black bile, yellow bile)—the Classical Era’s answer as to why people are the way they are.

Despite these and other sincere efforts, my 19th nervous breakdown arrived right on schedule at mid-life. Always a pushover for a self-understanding scheme with a numerical rubric, I signed up for an Enneagram workshop (from the Greek prefix ennea meaning nine).

Turns out, the nine-point personality system was my One True Thing.

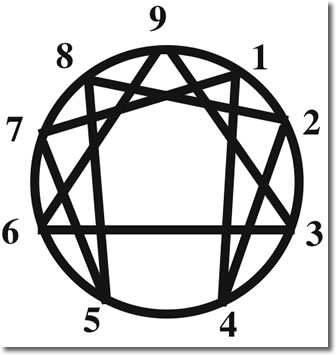

According to Helen Palmer, author of The Enneagram: Understanding Yourself and the Others in Your Life, the Enneagram is an ancient map to the nine basic personality filters. While it has its roots in the monastic traditions of the Middle East and Asia, the Enneagram corresponds to the nine psychological types recognized in today’s counseling professions: the Perfectionist, the Giver, the Performer, the Individualist, the Observer, the Investigator, the Enthusiast, the Protector and the Peacemaker.

“The Enneagram gives us a very clear map of the nine different ways we fall asleep to our lives and respond to life on automatic,” explains Sandra C. Smith, M. Div. and Certified Enneagram Consultant in Asheville, North Carolina. “When we respond to life from an automatic posture (to paraphrase Jesus) we do not have eyes to see and ears to hear.”

Smith says spirituality is as individual as personality. “Our journey to wholeness will involve a deeper understanding of both of these. Self-observation is key for personal growth and spiritual development. The foundational theological question is ‘Who am I?’”

Each of the nine personality types has a certain filter that guides one’s attention down a particular path. Do you know someone who has to have everything “just so”? How about the person who’s always at the center of some drama? What about someone who requires a lot of time to themselves? According to the wisdom of the Enneagram, each of these basic temperaments has its virtues and its vices, and no one type is “better” than any other.

Rather than offer another behavioral inventory, the study of the Enneagram goes deep toward discovering a person’s motivation and habits of attention. If we can understand what motivates us and how our attention is hijacked by our habitual responses, we can discover the direction in which our spiritual work needs to go.

“We really do have two selves, an automatic self and a present self,” Smith continues. “The automatic self, when we are in it, is in lockstep with our patterns and knee-jerk reactions, and we’ve fallen asleep to life. The automatic self sees reality through a specific filter that is shaped by our core fears and avoidances. This automatic self is really a contracted posture, both of the body and the heart, and it resists the present moment.”

“We really do have two selves, an automatic self and a present self,” Smith continues. “The automatic self, when we are in it, is in lockstep with our patterns and knee-jerk reactions, and we’ve fallen asleep to life. The automatic self sees reality through a specific filter that is shaped by our core fears and avoidances. This automatic self is really a contracted posture, both of the body and the heart, and it resists the present moment.”

Presence is the state in which spiritual growth is possible. “If I am awake and fully alive, I am resting in the lap of the holy, and when I move into a place of essence, I can offer love and compassion,” Smith explains. “When we are all there in our present self, type structure fades. When I am present, it is in that place of presence that I become receptive.”

At the two Enneagram workshops I attended, I discovered I am a Four, also known in various “Ennea-books”as the Individualist, the Tragic-Romantic, or Artistic temperament. (Because there are many teachers who have different names for each type, it’s more uniform and neutral to refer to someone as a Two or a Seven than with the descriptive nomenclature “Giver” or “Enthusiast,” which can be mistaken for a label.)

Fours value themselves for their individuality, their specialness, their originality. At the obnoxious end, the expression of our “terminal uniqueness” can be so aggressive that its turns people off. We are attracted to the extremes in life, and we are comfortable with despair and beauty, both our own and others’. A phrase like “the unbearable lightness of being” makes actual sense to a Four. What we’re not so great at, it seems, is doing ordinary stuff, like going to a job five days a week or tolerating an uneventful stretch in a relationship or task. In fact, the thought that another one out of every nine personalities is ALSO a Four is a massive affront to my Individualism with a Capital I.

At the end of the last workshop, Sandra Smith asked me, “Jill, what would your life be without drama?” My first thought was, “Dunh, I would cease to exist,” but I’m finding that’s not true.

When I take a step back from being a prisoner of shifting emotional states, what I find is that stillness feels pretty nice. When the people around me report that they are finding me too intense, I try to believe them. Drama, I’m finding at 50, is better indulged as a spectator sport than as a participant, so I’m getting my intensity from Battlestar Galactica on DVD and Wicked on tour. When I’m tempted to create some chaos, I try one of the breathing techniques I learned in the workshop and become present to whatever I’m feeling, and let that sadness or nostalgia or anger just have its voice. The description of a Four’s inner state “nailed” me closer than anything I’ve ever read, and I have hopes that I can move away from my investment in being seen as an “original” to a genuine connection with holy origin. Being present is not the same thing as being seen.

Copyright © 2009 Jill Piper.